20061031 Aloha from a Maui Haole

In contrast to what I usually do between my national park seasons, which is a whole lot of not very much, this year I am doing something that is at once the same and different. I am interpreting in a national park, not for the big money but for free, and not in any of the 49 states I have previously visited but in Hawaii.

In contrast to what I usually do between my national park seasons, which is a whole lot of not very much, this year I am doing something that is at once the same and different. I am interpreting in a national park, not for the big money but for free, and not in any of the 49 states I have previously visited but in Hawaii.Sabrina and Shane, interpreters I have worked alongside in both Katmai and Everglades, decided a few months back to volunteer for former Everglades maintenance wizard Mark Rentz. Mark is now at Haleakala National Park on Maui. That sounded like fun to me so I tagged along. Maintenance had no place for me so I am volunteering for the Interpretation Division. And loving it, I might add. I arrived on October 4th, and though much here merits mention I have been either too busy or too lazy to write.

Though not nearly as developed as Oahu, where Honolulu houses about a million people, most of Maui is not what it used to be. The changes began with the Polynesians bringing their favorite plants and animals about 2,000 years back and the changes have not stopped since.

Though not nearly as developed as Oahu, where Honolulu houses about a million people, most of Maui is not what it used to be. The changes began with the Polynesians bringing their favorite plants and animals about 2,000 years back and the changes have not stopped since.T

o see some of the old Maui, a person must rise above the lowlands 7,000 feet, toward Haleakala National Park and the chilly dry 10,000-foot summit of Haleakala volcano. [In the written Hawaiian language, which the ancient Hawaiians never had, the final 'a' in Haleakala should be topped with a macron. This diacritical mark indicates that the speaker should hold that vowel a bit longer and add a bit of stress to that syllable. Please bear with me as my Word '97 does not have the plug-in for Hawaiian.]

o see some of the old Maui, a person must rise above the lowlands 7,000 feet, toward Haleakala National Park and the chilly dry 10,000-foot summit of Haleakala volcano. [In the written Hawaiian language, which the ancient Hawaiians never had, the final 'a' in Haleakala should be topped with a macron. This diacritical mark indicates that the speaker should hold that vowel a bit longer and add a bit of stress to that syllable. Please bear with me as my Word '97 does not have the plug-in for Hawaiian.]Generally speaking Haleakala National Park [HALE in National Park Service shorthand] attempts to preserve within its boundaries Maui as the first Polynesians saw it. In this never-ending effort success does not come easy.

A fence of wooden posts and wire encircles the entire roughly 30,000 acres of HALE to keep out the unwanted fauna. Goats and pigs stay out but the axis deer, not yet at the park boundary, may be able to jump the fence. Mongoose, feral cats, rats and mice easily move back and forth. For them the Resource Management division maintains trap lines checked once or twice weekly.

These critters inside the fence threaten the adults, chicks, and/or eggs of the world's rarest waterfowl, the Ne Ne goose. I loosely use the term waterfowl as the Ne Ne live in shrub forest. Developers have eliminated any suitable watery habitat. The Ne Ne disappeared from Maui at one time and were reintroduced in the early 1960s. Currently about 300 birds live here, a small but stable population.

These critters inside the fence threaten the adults, chicks, and/or eggs of the world's rarest waterfowl, the Ne Ne goose. I loosely use the term waterfowl as the Ne Ne live in shrub forest. Developers have eliminated any suitable watery habitat. The Ne Ne disappeared from Maui at one time and were reintroduced in the early 1960s. Currently about 300 birds live here, a small but stable population.Native forest birds also have a tough time here. Most of them descend from a common ancestor, thought to be a finch-like bird. Like Darwin's finches on the Galapagos Islands, the Hawaiian honeycreepers are now adapted to fill available niches and vary greatly in color and bill shape. At least those that have not gone extinct. Ancient Hawaiians hunted them for their colorful plumage and Europeans cut down their forest homes. They have died from avian malaria transmitted by introduced mosquitoes that previously bit infected introduced birds.

Maui has no native reptiles or amphibians, though geckos and toads are here now. Thank goodness snakes, especially the Brown Tree Snake plaguing Guam, have not been able to get a foothold here.

Maui has no native reptiles or amphibians, though geckos and toads are here now. Thank goodness snakes, especially the Brown Tree Snake plaguing Guam, have not been able to get a foothold here. A great many non-native plants have established on Maui. Most of the lowlands could be South America, Central America, or Southeast Asia. While the park has its problems with exotic plants, the cool climate and lack of suitable substrate prevent most from taking over in the higher dryer areas.

A great many non-native plants have established on Maui. Most of the lowlands could be South America, Central America, or Southeast Asia. While the park has its problems with exotic plants, the cool climate and lack of suitable substrate prevent most from taking over in the higher dryer areas.  A yellow-flowered evening primrose seems to be able to grow with just a tiny bit of soil. Still, in the rocky arid "crater" natives like Nahe Nahe dominate, if a shrub here and there can be termed domination.

A yellow-flowered evening primrose seems to be able to grow with just a tiny bit of soil. Still, in the rocky arid "crater" natives like Nahe Nahe dominate, if a shrub here and there can be termed domination.

Brazilian Pepper, one of the banes of the Everglades, is making inroads in the lower wetter areas of the park.

These places are home to a number of non-native plants important to the native Hawaiians. The park stresses preservation of culture here, so some of the aliens, like breadfruit, may be allowed to stay.

These places are home to a number of non-native plants important to the native Hawaiians. The park stresses preservation of culture here, so some of the aliens, like breadfruit, may be allowed to stay.

If the plants and animals they brought are considered alien, can the people themselves be considered native? I guess some of them can while others cannot.

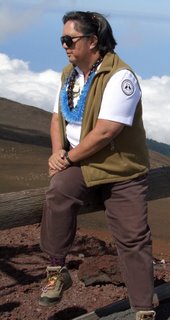

If the plants and animals they brought are considered alien, can the people themselves be considered native? I guess some of them can while others cannot.  Even among park staff some interpreters are native,

Even among park staff some interpreters are native,  some have been here long enough to be naturalized, and still others are definitely haole.

some have been here long enough to be naturalized, and still others are definitely haole.

While the story we like to tell is that of endangered native species and non-native interlopers, what people most want to hear about is the "crater".

When is a crater not a crater? When it is a valley, which this one is. Wind, water in various forms, and earthquakes combined to erode the original Haleakala summit long ago. The current valley rim sits at least 3,000 feet below the original summit and the valley floor was once almost 6,000 feet below the rim. Eruptions subsequent to the major erosion have partially filled the valley with lava and cinder.

When is a crater not a crater? When it is a valley, which this one is. Wind, water in various forms, and earthquakes combined to erode the original Haleakala summit long ago. The current valley rim sits at least 3,000 feet below the original summit and the valley floor was once almost 6,000 feet below the rim. Eruptions subsequent to the major erosion have partially filled the valley with lava and cinder. Looking east into the "crater", which common usage dictates we call it, we see a wind-blown desert, a dry landscape lying in the rainshadow created by the north and east rims.

Looking east into the "crater", which common usage dictates we call it, we see a wind-blown desert, a dry landscape lying in the rainshadow created by the north and east rims.  Just over the rim on the far side of the crater lies a different world, a lush wet world that may receive over 400 inches of rain annually.

Just over the rim on the far side of the crater lies a different world, a lush wet world that may receive over 400 inches of rain annually.A number of celebrities maintain homes on the wet side. Oprah Winfrey bought here planning to build a resort. Local opposition stopped her, so she has bought elsewhere on the island.

Charles Lindbergh sought refuge here to isolate himself from a tragic life. His grave has become a selling point for tours to the area.

Charles Lindbergh sought refuge here to isolate himself from a tragic life. His grave has become a selling point for tours to the area.In every grocery store, convenience store, gas station and restaurant on Maui you'll find a collection of free brochures touting the must-dos during a visit here. You must give money to enjoy the activities listed, and the publications include advertisements from organizations just waiting to take it from you.

On every Top Ten List of Things to Do on Maui you'll find mentioned a sunrise visit to the Haleakala summit. In fact, this seems to be mandatory. Any given morning you'll find the summit parking area filled to overflowing with tour buses and rental cars.

Underdressed throngs shiver at the rim, draped in hotel bedding, waiting for the first rays to find their way to the House of the Sun, the literal meaning of Haleakala. [Failing to stress the final syllable will result in "Raspberry House".]

Underdressed throngs shiver at the rim, draped in hotel bedding, waiting for the first rays to find their way to the House of the Sun, the literal meaning of Haleakala. [Failing to stress the final syllable will result in "Raspberry House".]As appealing as it sounds,

House of the Sun does not tell the whole story. The House of the Sun can also be the

House of the Sun does not tell the whole story. The House of the Sun can also be the  House of Clouds, the House of

House of Clouds, the House of  Color and

Color and  Gray, and the

Gray, and the  House of Shadow and Light.

House of Shadow and Light.Just as it attracts us today, the House of the Sun attracted ancient Hawaiians. Among the reasons was the unmatched view of the heavens. The Hawaiians trekked to the summit to study the stars for the purpose of celestial navigation.

Humans continue to study space from the top of Haleakala. An observatory complex known as Science City sits just outside the park. From here the US Air Force tracks near space objects for defense purposes. The University of Hawaii and many others learn more about the moon, the sun, and other points far beyond this national park.

Humans continue to study space from the top of Haleakala. An observatory complex known as Science City sits just outside the park. From here the US Air Force tracks near space objects for defense purposes. The University of Hawaii and many others learn more about the moon, the sun, and other points far beyond this national park.I shall be far beyond this national park as well, in a little better than a week.

Far away from an awe-inspiring place and warm caring people who have made me feel a part.

Far away from an awe-inspiring place and warm caring people who have made me feel a part.  I'll be heading for the temperate San Francisco Bay Area. From California I begin the annual wheeled migration to Florida's Everglades. Within a single calendar year I shall have lived in Alaska, Hawaii, California, and Florida--each place strikingly different from the others.

I'll be heading for the temperate San Francisco Bay Area. From California I begin the annual wheeled migration to Florida's Everglades. Within a single calendar year I shall have lived in Alaska, Hawaii, California, and Florida--each place strikingly different from the others.

.jpg)