20061204 Soup and Crackers

20061204 Soup and Crackers

Several years ago I was lucky enough to have met long-time Miami resident Ellen Siegel, a remarkable, larger-than-life friend of Everglades National Park. In addition to volunteering many hours directly for the park as a first-rate naturalist and persuading doubting Miami folk to visit the seemingly-frightful swamp in their back yard, each year Ellen opens her home and her heart to a new batch of seasonal NPS naturalists.

We naturalists may be comfortable with eagles and osprey but take us to Miami and we become pigeons, easy prey for unscrupulous businesspeople. Ellen offers to connect us with reliable doctors, dentists, and car mechanics. We can use her driveway as a park-and-fly lot for out-of-town trips. She’ll always return a call for a restaurant reference or driving directions despite a blinding-speed schedule of personal and professional commitments. Speaking of professional, Ellen operates a financial planning firm and provides pro bono financial planning services for park people. What Ellen recently provided Nick, like me a seasonal NPS naturalist, and me was opportunity.

The Miccosukee Indians [they prefer that term] lived on hammocks, islands of high and dry ground in the otherwise wet marshes and swamps of Everglades and Big Cypress, for well over a hundred years. Some still do.

In more recent decades some of these remote hammocks began to be used as fishing and hunting camps by non-Indian folks living in town. Swamp buggies and airboats carried them sometimes many miles from the nearest road.

For years I had heard of these camps and presumed them to be primitive, perhaps a shack or two, peopled by Florida Crackers, a term having multiple meanings and in this case roughly translating to rednecks. I say this with Jeff Foxworthy fondness.

Ellen, who’s circle of friends and acquaintances seems as vast the Everglades itself, knows one of these rough-and-tumble don’t-tread-on-me characters, a Vietnam-era veteran and former helicopter pilot by the name of Jimmy Rhodes, born and raised in south Florida. Jimmy owes a debt to his uncle.

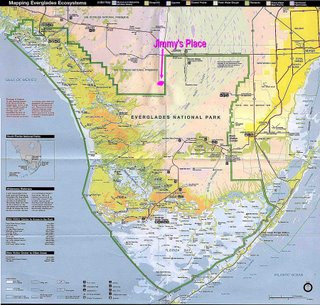

Ellen, who’s circle of friends and acquaintances seems as vast the Everglades itself, knows one of these rough-and-tumble don’t-tread-on-me characters, a Vietnam-era veteran and former helicopter pilot by the name of Jimmy Rhodes, born and raised in south Florida. Jimmy owes a debt to his uncle.Jimmy’s family had been using a hammock in the wetlands west of Shark River Slough for some years. Jimmy’s uncle decided the time had come to make it legal and acquired a deed to the property before it became part of Big Cypress National Preserve in 1974.

Today Jimmy is a private inholder within the National Preserve and must be given access across the Preserve to reach his property.

Today Jimmy is a private inholder within the National Preserve and must be given access across the Preserve to reach his property.Now Jimmy has few fond words for the National Park Service and park rangers. At his camp he proudly posts a quote attributed to Red Cloud. "They made us many promises, more than I can remember, but they never kept but one; they promised to take our land and they took it."

Jimmy has clarified who "they" are by penciling in "The National Park Service" above the quote, and further states who he is by adding the name Rhodes after Red Cloud.

Jimmy has clarified who "they" are by penciling in "The National Park Service" above the quote, and further states who he is by adding the name Rhodes after Red Cloud.Thus I feel pretty certain that Jimmy is not in the habit of inviting rangers to his camp.

Miracle worker Ellen persuaded him to allow fellow-ranger Nick and me to accompany her on a day-trip to Jimmy’s little bit of paradise in the Big Cypress.

Miracle worker Ellen persuaded him to allow fellow-ranger Nick and me to accompany her on a day-trip to Jimmy’s little bit of paradise in the Big Cypress.Created in 1974, the Big Cypress National Preserve has rules different from nearby Everglades National Park. Recreational use trumps resource protection, at least it did until fairly recently.

You may have seen aerial photos depicting a wetlands criss-crossed by airboat trails and swamp buggy tracks. This is Big Cypress. Within the last few years the National Park Service implemented new rules requiring the off road vehicles to stick to established trails.

You may have seen aerial photos depicting a wetlands criss-crossed by airboat trails and swamp buggy tracks. This is Big Cypress. Within the last few years the National Park Service implemented new rules requiring the off road vehicles to stick to established trails.I must admit that I have been critical of those users of the Big Cypress who over the years had degraded the natural system. Now I was to spend the day with one of these very people. Ellen advised me to be a polite guest. I had every intention of minding my Ps and Qs.

At an airboat launch area in the Preserve, Ellen, Nick, and I met Jimmy and his 11-year-old grandson Taylor for the 40-minute skim through the sawgrass.

Jimmy was quite polite himself, as if Ellen had cautioned him about not offending the tree huggers.

Jimmy was quite polite himself, as if Ellen had cautioned him about not offending the tree huggers.This was to be my second experience riding an airboat. Last year, as part of training, the Flamingo district naturalist staff attended a commercial airboat tour. If the commercial trip was a drag race, Jimmy’s ride was a commute to work.

Relatively slowly and with great skill he guided the small craft, top heavily laden with five people and gear, across water only inches deep and over some spots of almost-dry land. In a shout designed to be heard through foam earplugs and the mickey mouse "ears" worn by workers on the airport tarmac, I asked if piloting helicopters and airboats were similar experiences. "Well, they’re both noisy!" he shouted back.

Relatively slowly and with great skill he guided the small craft, top heavily laden with five people and gear, across water only inches deep and over some spots of almost-dry land. In a shout designed to be heard through foam earplugs and the mickey mouse "ears" worn by workers on the airport tarmac, I asked if piloting helicopters and airboats were similar experiences. "Well, they’re both noisy!" he shouted back. The din is one of the reasons that in general Everglades National Park bans airboats. The sound and the boat itself frighten wading birds—we flushed hundreds during our journey. We also flattened forever many blades of sawgrass, the signature grass [botanically a sedge] of the "River of Grass" known as the Everglades.

The din is one of the reasons that in general Everglades National Park bans airboats. The sound and the boat itself frighten wading birds—we flushed hundreds during our journey. We also flattened forever many blades of sawgrass, the signature grass [botanically a sedge] of the "River of Grass" known as the Everglades.  The irony was that the herons and egrets and ibis and woodstorks we rousted from their feeding were by-and-large feeding along the airboat trail. Evidently the birds find catching fish easier where the sawgrass has been cleared.

The irony was that the herons and egrets and ibis and woodstorks we rousted from their feeding were by-and-large feeding along the airboat trail. Evidently the birds find catching fish easier where the sawgrass has been cleared.After about thirty minutes of zigging and zagging around tree islands a neighbor’s fishing/hunting camp in to view.

My preconceived notion of a camp blew away with the warm breeze. Instead of a leaning shack with a tar paper roof I saw a tidy pale green bungalow trimmed in white. How did this get way out here? As nice as the neighbor’s place was, Jimmy’s little bit of paradise would blow me away.

My preconceived notion of a camp blew away with the warm breeze. Instead of a leaning shack with a tar paper roof I saw a tidy pale green bungalow trimmed in white. How did this get way out here? As nice as the neighbor’s place was, Jimmy’s little bit of paradise would blow me away. Somehow, without the use of aircraft, Jimmy and his family have managed to transport to a bit of high ground, several miles from any road and surrounded by water, the materials for a two-story house—complete with a large billiard table[!], a one room house, a generator shed, and an outhouse. Three generators power lights and air conditioning and TV.

Somehow, without the use of aircraft, Jimmy and his family have managed to transport to a bit of high ground, several miles from any road and surrounded by water, the materials for a two-story house—complete with a large billiard table[!], a one room house, a generator shed, and an outhouse. Three generators power lights and air conditioning and TV. The refrigerator runs on propane. Holey moley! Civilization amidst wilderness.

The refrigerator runs on propane. Holey moley! Civilization amidst wilderness.

After Taylor led us on a walk through the hardwood hammock, which would cover the entire tree island were it not for the buildings, Jimmy showed us the house. The view from the second floor is quintessential Everglades.

After Taylor led us on a walk through the hardwood hammock, which would cover the entire tree island were it not for the buildings, Jimmy showed us the house. The view from the second floor is quintessential Everglades.

We were invited to share in a hot lunch Jimmy prepared. While we shared a table, the vegetarian habit prevented Ellen and I from sharing the food.

We were invited to share in a hot lunch Jimmy prepared. While we shared a table, the vegetarian habit prevented Ellen and I from sharing the food.  During the meal Jimmy began to spew the bile that had been produced by years of dealing with authorities in general and the National Park Service in particular.

During the meal Jimmy began to spew the bile that had been produced by years of dealing with authorities in general and the National Park Service in particular. No longer could he operate his airboat and swamp buggy wherever he pleased. He had to pay use fees to access his own land. He felt that, with the exception of limiting development, the NPS had done everything wrong when it came to protecting the swamps and marshes.

No longer could he operate his airboat and swamp buggy wherever he pleased. He had to pay use fees to access his own land. He felt that, with the exception of limiting development, the NPS had done everything wrong when it came to protecting the swamps and marshes. And that is when it hit me. Jimmy and I are about as different as two people can be, but we share something in common. We both want to save the wetlands of south Florida. We have our biases but in the end we want the same thing, a healthy ecosystem.

And that is when it hit me. Jimmy and I are about as different as two people can be, but we share something in common. We both want to save the wetlands of south Florida. We have our biases but in the end we want the same thing, a healthy ecosystem.  We are a couple of crackers in the same soup bowl. I feel lucky to have met him.

We are a couple of crackers in the same soup bowl. I feel lucky to have met him..jpg)