20060829 Amalik Bay/Geographic Harbor Trip Part 5 Hygiene and Sanitation

I admit I have bought into the American norm of cleanliness, five days a week. For years I have showered and shaved every workday. Heaven forbid that I should stink professionally. My days off are another matter.

I admit I have bought into the American norm of cleanliness, five days a week. For years I have showered and shaved every workday. Heaven forbid that I should stink professionally. My days off are another matter.Camping and backpacking are another matter as well. Over the years I have made little attempt at personal hygiene while living primitively among friends. What did it matter if I stank when all of us stank?” We adopted a different standard for a different circumstance. This was the rationalization anyway.

Roughing it at the Amalik Bay cabin was different. Each day Niki and I appeared before the public in the NPS uniform as official representatives of the United States Government. Our public, in this case bear viewers at Geographic Harbor, had the previous night slept in a motel room with a hot shower, Dial, Pert, and Arrid XX. We were living primitively while our public still used the cleanliness standard for the civilized world. What to do?

Shaving certainly was not an issue for me, as I have not shaved most of my face for over four months. Failing to shave my neck for a few days hardly mattered.

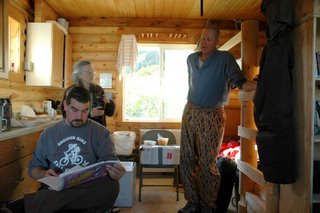

Staying clean otherwise was a problem. Most times cool temperatures and dreary if not rainy skies discouraged outside sponge baths and indoors a person found no privacy. Niki took the opportunity to grab my camera and document my one attempt to bathe at the kitchen sink.

Jason took the plunge into the bay once and was chilled for some time after the experience. After our boat training swim in 33 degree Naknek Lake back in May, I was in no hurry to join him. Each day, though, I did wash my face and brush my teeth at the bay.

Jason took the plunge into the bay once and was chilled for some time after the experience. After our boat training swim in 33 degree Naknek Lake back in May, I was in no hurry to join him. Each day, though, I did wash my face and brush my teeth at the bay.Monday evening Niki and I had the unexpected pleasure of showering aboard a 120-passenger cruise ship, in the captain’s cabin no less. We awoke Monday morning to find the “SS Spirit of Oceanus” anchored in Amalik Bay not far from our cabin. As the skiff carried us to another day of watching bears and distributing surveys at Geographic Harbor, Al explained that the cruise ships usually request for a naturalist to come on board to address the passengers.

Light rain fell for the entire time Niki and I “worked.” I’m sure we looked a soggy mess when Al and Jason retrieved us for the journey back to the cabin on Amalik Bay. Rain continued falling as we passed the cruise ship, still at anchor, on our way home. At the beach below the cabin, Al mentioned in his understated way that the captain of the SS Spirit of Oceanus has indeed requested naturalists. Would we be interested?

Light rain fell for the entire time Niki and I “worked.” I’m sure we looked a soggy mess when Al and Jason retrieved us for the journey back to the cabin on Amalik Bay. Rain continued falling as we passed the cruise ship, still at anchor, on our way home. At the beach below the cabin, Al mentioned in his understated way that the captain of the SS Spirit of Oceanus has indeed requested naturalists. Would we be interested? You might as well ask a child if she wants candy. Of course we were interested! But wouldn’t these people be more interested in hearing about Jason and Al’s adventures as law enforcement type rangers than hearing about the origin of the park from a couple of Katmai rookies? Perhaps so, but neither Jason nor Al had interest in sharing. Let’s turn this boat around!

You might as well ask a child if she wants candy. Of course we were interested! But wouldn’t these people be more interested in hearing about Jason and Al’s adventures as law enforcement type rangers than hearing about the origin of the park from a couple of Katmai rookies? Perhaps so, but neither Jason nor Al had interest in sharing. Let’s turn this boat around!At the ship’s fantail, a low platform at the stern for loading and unloading, Captain Ivan himself met us and directed the boson to take our things. We opted to carry them ourselves, not wanting to impose. Captain Ivan most graciously escorted Niki and I to the bridge, with all of its fancy navigational gadgetry, for a look around. Was there anything he could do for us? Well, yes there was. We have been in the rain and mud all day. Would we be able to clean up a bit before appearing before your passengers?

Whereupon we were whisked to his cabin and directed to the hot shower, complete with Dial, Pert, and Arrid XX. Wow! The VIP treatment! If he only knew how tenuously Niki and I clung to the bottom rungs of the National Park Service ladder. Of course neither of us planned to tell him.

From the captain’s cabin we were led to the ship’s lounge, where the captain himself asked, “Can I get you a cappuccino?” Our table was laid with fresh-baked cookies and chocolate pie.

Both Captain Ivan and Jen, the activities director, were as curious about ranger life as Niki and I were curious about life aboard a cruise ship. Turns out the Spirit of Oceanus had already been to the Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia and several points further north in Alaska before reaching Amalik Bay.

The passengers too were interested in the park rangers. A couple joined us at our table while a number of others listened from nearby. At six pm we began the formal program.

It seems we were to be the cocktail hour entertainment. Ninety-eight passengers filed in to hear the rangers talk while they sipped their bourbon and drank their wine. A number of crewmembers joined the audience as well. What a treat after presenting Brooks Camp evening programs all summer to just a handful of people.

If we are working the lounge, we might as well use lounge material. I gave a 15-minute presentation on the significance of Katmai National Park, Niki spoke for a few minutes about her life and times commercial fishing, then we opened it up to questions. We inserted as much ranger schtick as possible the entire 45 minutes of our show and the audience loved it. You’d have thought we were in the Catskills. At times like this I curse the ranger ethic that will not allow us to accept tips.

A couple of passengers asked if we would be joining them for dinner, whereupon Jen stepped in to explain that we had to be going. Well, that was almost true. They were the ones that had to be going, with an 8 pm sail time to head for Kodiak Island and dinner yet to be served. Instead of the captain’s table, Jen took us to the crew mess for a buffet meal.

Did we ever chow down in the few minutes we had to eat before it was anchors aweigh! As the regular fare mooed, oinked, and clucked a bit too much for my taste, the cook prepared a vegetable stir-fry over rice especially for me. Yum, yum!

But I digress from today’s topic, which was…oh yes, hygiene and sanitation. One aspect of hygiene and sanitation brought forth an ethical dilemma. As we toted all fresh water from a small waterfall ¼ mile away, we conserved every drop. Still, the byproduct of dishwashing and tooth brushing was gray water. What to do with it in this pristine wilderness?

Green extremists will tell you that gray water can be cooked and tea added for a beverage. Hmmm. Our 5-gallon pail sitting beneath the sink was ½ full of sludge every other day. That’s a lot of tea, no matter how tasty it might be.

An alternative to drinking the stuff is to fling it outside so as to spread the bits over a large area. Hmmm again. Of the four of us, three slept inside the cabin while only one slept outside in a tent in brown bear country without the protection of an electric fence. Let’s see, who might that one brave soul be? It was bad enough that, weather permitting, the others took their meals on the porch, sprinkling crumbs ten feet from my nylon abode. I certainly did not want a greasy concoction of food scraps and soap flung anywhere near the cabin.

Al’s solution, which on its face seems environmentally insensitive, worked best. He dumps the gray water into the deep waters and extreme tides of Amalik Bay, which also served as our urinal. I suppose if a permanent community of a thousand people practiced this method of waste water management the sea might feel the impact, but not from the waste created by at most four people for a few weeks a year. At least this is the rationalization. Needless to say, I was careful to execute my aforementioned daily bayside washing routine well away in distance and time from the wastewater disposal area.

As for solid waste, floatplanes fly out the garbage to the town of King Salmon where it ends up in a landfill. For human solid waste we enjoyed the freedom of a one-holer set behind the cabin.

As for solid waste, floatplanes fly out the garbage to the town of King Salmon where it ends up in a landfill. For human solid waste we enjoyed the freedom of a one-holer set behind the cabin.  Plenty of fresh air and no flushing required. Comes complete with aerosol spray of the cayenne pepper scent and a breathtaking view of Amalik Bay

Plenty of fresh air and no flushing required. Comes complete with aerosol spray of the cayenne pepper scent and a breathtaking view of Amalik Bay  thanks to a bear having ripped off the door.

thanks to a bear having ripped off the door.  A piece of pressboard held up by a couple of 1x4s preserves modesty.

A piece of pressboard held up by a couple of 1x4s preserves modesty.I guess I still have not addressed the body odor issue. Well, the cruise ship shower kept me from being malodorous for a couple of days. From then on I made do with a fresh t-shirt every day and arms kept pressed to my sides. I suppose I did stink by the end of the week, but this is Alaska where many American norms are ignored. At least this is the rationalization.

.jpg)